LATEST UPDATE

As of January 2020, Blue Water claims are being processed. List of Navy Ships in Vietnam War here!

November 26, 2018 UPDATE

Gray v. Wilkie

First, a quick recap of what’s happened. In February of 2016, the Court of Appeals for Veterans’ Claims (CAVC) threw out the VA’s definition of inland waterways and instructed the VA to re-evaluate the definition. The VA did so by making a revision to their M21-1 Manual (this is where the VA publishes their policies and procedures for VA disability claims). In the revision, the VA defined inland waterways to “end at their mouth or junction to other offshore water features.” The effect? The manual revision excluded all ports, harbors and open waters from the presumption of Agent Orange Exposure. Mr. Gray asked the Federal Circuit to review the manual revision, but the Federal Circuit held it lacked the authority to review a VA interpretative rule if that rule was published in the M21-1 Manual.

After the Federal Circuit ruling, the next step was to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. However, the U.S. Supreme Court won’t look at every case that comes its way. Before the U.S. Supreme Court will even accept a case, the claimant must file what is called a petition for writ of certiorari. In other words, you have to prove to the Supreme Court why they should hear your case. The Supreme Court only accepts approximately 2.8% of the cases that are seeking review.

On Friday November 2, 2018 the U.S. Supreme Court granted Mr. Gray’s petition for writ of certiorari. They will address the issue of whether or not the Federal Circuit has the authority to review VA rules that are published in the M21-1 Manual. Oral argument for Mr. Gray’s case is expected to take place in February 2019.

Procopio v. Wilkie

Similar to the Gray case, this case involves a Blue Water Navy veteran and the presumption of exposure to Agent Orange. In the Procopio case, the issue involves the meaning of the “Republic of Vietnam” is in relation to the Agent Orange Act of 1991. The veteran, Mr. Procopio, is arguing that the Republic of Vietnam should include territorial seas.

In support of this argument, Mr. Procopio’s position is that Congress’ intent to include service off the coast of Vietnam (in the territorial seas) when they used the phrase “Republic of Vietnam” in the Agent Orange of 1991. The United Nations has determined that the territory of a sovereign nation includes waters 12 nautical miles off the coast of the country’s landmass.

Mr. Propocio’s case is currently pending oral argument before the Federal Circuit. If the Federal Circuit decides in his favor, this would mean the presumption of Agent Orange exposure would HAVE to extend to veterans who served aboard ships off the coast of Vietnam.

Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act

Introduced into the House in January of 2017, this bill seeks to extend the Agent Orange presumption of exposure to Blue Water Navy veterans. In June of 2018, the bill passed unanimously in the House. The House even negotiated a plan to pay for the benefits that would be owed to thousands of Blue Water Navy veterans.

The next step? The bill has to pass the Senate. Before it can pass, however, there has to be a vote in the Senate. Unfortunately, this vote is being stalled. The VA has given testimony on the bill at a Senate Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, and this testimony was certainly not in favor of the bill. This has resulted in the Senate Committee Chairman Johnny Isakson delaying the vote on the bill, stating there is more work to do to understand the parts of the bill. Senator Isakson once appeared to endorse the bill, however things are now more uncertain after the strong opposition from the VA.

February 12, 2016 UPDATE

The VA Releases Revised Provision on the Brown Water vs. Blue Water Line

On February 5, 2016 the VA released their revised provision regarding the definition of Vietnam inland waterways. This change came after the CAVC found the VA’s prior definition of inland waterways was arbitrary and capricious and therefore invalid. Unfortunately, the VA has decided to rule against veterans again. The revised provision provided a definition of “inland waterways” without providing any kind of rationale. Additionally, the VA’s revised rule on brown vs. blue water completely ignored the CAVC’s instructions that came out of the Gray case. In the Gray case, the CAVC ordered the VA to consider the locations where Agent Orange was sprayed when making their determination of what constituted an inland waterway. In the February 16th revision, the VA was silent on the matter of the spraying of Agent Orange. Rather, they limited their discussion to fresh water vs. salt water.

Specifically, the VA’s provision now defines and inland waterway as “freshwater rivers, streams, and canals, and similar waterways.” The VA now considers inland waterways to “end at their mouth or junction to other offshore water features.” For rivers and other waterways that end on a coastline, the VA said that the end of the inland waterway shall be determined by “drawing a straight line across the opening in the landmass leading to the open ocean or other offshore water feature such as a bay or inlet.” In other words, the VA is saying that they draw the line right at the point where the mouth of the river touches the harbor, bay, or inlet. The following locations meet the criteria for inland waterways according to the new provision:

- All rivers, from their mouth on the coast, or junction with adjoining coastal water feature, and throughout upstream channels and passages within Vietnam

- All streams

- All canals

- All navigable waterways inside the perimeter of land-type vegetation (for example, trees and grasses, but not seaweed or kelp).

The new provision defines offshore waters (blue water) as “the high seas and any coastal or other water feature, such as a bay, inlet, or harbor, containing salty or brackish water and subject to regular tidal influence.” The definition includes “salty and brackwish waters situated between rivers and the open ocean.” The new provision specifically lists the following harbors and bays to be offshore waters:

- Da Nang Harbor

- Nha Trang Harbor

- Qui Nhon Bay Harbor

- Cam Ranh Bay Harbor

- Vung Tau Harbor

- Ganh Rai Bay

Another notable part of the new provision is the VA no longer will extend the presumption of exposure to herbicides to veterans serving aboard vessels that entered Qui Nhon Bay Harbor or Ganh Rai Bay. For those veterans that served in Qui Nhon Bay or Ganh Rai Bay during specified time periods aboard ships that are already on the VA’s list of brown water ships, the VA will continue to extend the presumption of exposure. However, with the new provision in place, the VA will no longer add vessels to their list of brown water ships, nor will they add any more dates to the list.

In summary, it seems the VA has decided that the difference between brown water (inland waterways) and blue water (offshore waters) comes down to brown water being freshwater and blue water being salt water or a mixture of salt and freshwater (brackish water). However, what the VA failed to do was provide any kind of reasoning for why they made this distinction. The provision doesn’t reference any kind of information regarding why salt water apparently has some kind of effect of the toxicity of Agent Orange.

The VA has yet again provided an arbitrary and capricious determination of what constitutes an inland waterway. Not only does the VA fail to provide the required explanation and rationale for its interpretation of inland waterways in Vietnam, they also completely contradict what the CAVC ordered in the Gray case. Although the new provision is not what we had hoped for, this is not the end of the road. We will contest this interpretation in the Courts again.

Sept 10, 2015 UPDATE

In this webinar, Matthew Hill and Commander John Wells, Esq., the Executive Director, Military-Veterans Advocacy, Inc., cover what has and hasn’t changed in the Brown Water/Blue Water Debate.

April 27, 2015 UPDATE

Watch Mr. Gray and Matthew Hill discuss the case on the TV appearance of Mr. Gray on Newsmax

April 24, 2015, UPDATE

Veterans Court throws out VA’s interpretation of Inland waterways in Vietnam.

Mr. Gray, after being rejected for more than seven years, has now finally received the first positive decision in his case. VA has maintained that it does not have to compensate sailors with diseases related to Agent Orange whose ships entered Vietnamese ports such as Da Nang harbor and Cam Ranh Bay because they were not inland waterways. VA reasoned that these ports were not inland waterways because these harbors were deeper and open to the sea and not inland like rivers which would have contained Agent Orange in their runoff.

The Veterans Court dismissed VA’s reasoning as inconsistent and irrational. It found that the reasoning was inconsistent with VA’s regulation for Agent Orange, which stated that veterans on land or in inland waterways in Vietnam are entitled to compensation benefits for certain diseases. The regulation’s purpose was to give benefits to veterans exposed to Agent Orange. Here, the Court found that VA’s stated reasoning for not including harbors, because they were deeper than rivers, had no connection to likelihood of exposure.

The Court next turned to the fact that VA’s reasoning was irrational. VA found that some bays were inland and others were not and gave no rational basis for doing this. The Court reviewed maps of several rivers and bays and could not determine why VA deemed some to be inland and others not. The Court pointed to the fact that VA did not even define what the mouth of a river is and how far it extends into the sea. The Court noted that VA has the ability to interpret its regulation, but it cannot do so by what appears to be just flipping a coin.

When it came to the remedy the Court did not reverse VA’s finding that a harbor is not an inland waterway. It stated that VA is authorized to make this determination, so even though the interpretation VA made in this case was not valid, VA will be allowed to make a new determination as to what an inland waterway is. This is not the outcome that Mr. Gray pushed for. It is Mr. Gray’s position that the Veterans Court has the authority not only to throw out VA’s current interpretation, but also decide what the proper interpretation is. This is a question of law, not an issue of fact.

The Court is sending the case back to VA to re-interpret its regulation. The court did not set a time limit for this interpretation, nor is there any indication as to how many times VA is going to be allowed to re-interpret its regulation. Before the case goes back to VA to re-interpret its regulation, VA has 120 days to decide if it wants to appeal the decision to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

The Court also threw out Mr. Gray’s argument under the Constitution’s equal protection clause that he should receive benefits because he was in the same position as another veteran that received benefits from the BVA when, in 2009, it found that Da Nang harbor was an inland waterway. The Court did so because it concluded that the 2009 BVA decision stated that the veteran was on a ship that was listed on the Agent Orange registry as having gone up the Saigon River, and because there was credible evidence that the veteran went ashore while in Da Nang harbor. The Court distinguished the 2009 case from Mr.Gray’s case despite the fact that the BVA unequivocally found that the veteran was entitled to Agent Orange benefits because he was in an inland waterway, Da Nang Harbor.

The takeaways from Mr. Gray’s case:

- This decision is a small first step in the battle for the veteran sailors fighting for the benefits they deserve from being exposed to Agent Orange in any inland waterway of Vietnam. The Court understood that VA’s interpretation of inland waters was invalid and threw it out. But it decided to allow VA to re-interpret the regulation in a seemingly endless fashion. Work on all cases where a veteran is fighting VA to classify a body of water in Vietnam as an inland waterway will stop until VA makes its new interpretation on what inland waterway means. The Court put no timeline on VA to do this.

- The Court left the door open for other veterans to obtain benefits under the equal protection clause of the Constitution in the two ways that it found that Mr. Gray’s case was different from the veteran in the 2009 decision.

- First, it distinguished Mr. Gray from the 2009 case by saying that there was credible evidence that the 2009 veteran went ashore. The BVA decision stated there was credible evidence of the veteran going ashore but not corroborating evidence. A veteran can be credible in his statement but, usually, to prove service connection, he still needs another person or document to corroborate (i.e. back up) what he is saying. Here, the Court seems to say that all he needs is credible evidence, which could be just the veteran’s word.

- Second, is the Court’s use of the inland waterways registry. Currently, VA will only give benefits for those veterans on a ship on the inland waterways registry if they were on the ship when it was in an inland waterway, not after. The Court here seems to indicate that if a veteran was on a ship at any time after the ship entered an inland waterway then he is presumed to have been exposed.

- Getting VA to recognize the exposure of all these veterans serving in bays and harbors is a fight we must take to Congress and to VA itself. There currently is legislation being pushed in the House and Senate to extend the presumption to these veterans. VA itself is at a point where it understands that it needs to be more pro-veteran. This is an opportunity to reach out to and educate the current leadership about the injustice of this issue.

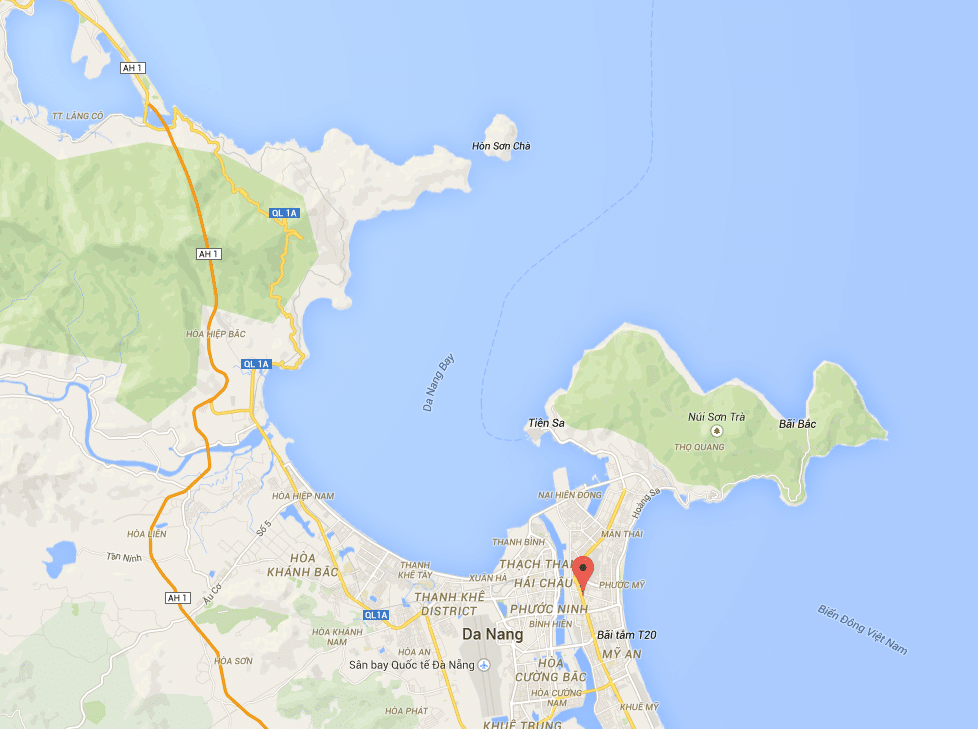

The Da Nang Harbor Case

On February 25, 2015, a panel of three judges from the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims heard oral argument in the case of Gray v. McDonald (13-3339). The central issue in the case was whether the Da Nang Bay, including Da Nang Harbor, of Vietnam was an inland waterway or a deep water port. The distinction has significant meaning for the tens of thousands of veterans whose ships entered the port. If the harbor is identified as an inland waterway then those veterans are covered by the presumption of being sprayed by Agent Orange, which entitles them to service connected compensation for the presumptive disabilities caused by Agent Orange as listed under 38 CFR 3.309(e). If Da Nang Harbor is considered a blue water or deep water harbor then the veterans are not covered under the Agent Orange legislation. As a result, any and all Agent Orange disabilities that those veterans suffer from would not be covered.

Unfortunately, the VA has determined that the major harbors in Vietnam—Da Nang Harbor, Cam Ranh Bay, and Vung Tau—were open deep-water harbors. It was in the face of this policy that Mr. Gray has fought his way through the system. Every VA adjudicator to review his case has denied him the benefits for his Agent Orange related diseases because he was in an open deep-water harbor and he did not leave the ship and step on the ground of Vietnam. Mr. Gray has taken this case to the Court of Appeals of Veterans Claims to seek justice for his case. Now he has a chance to correct this anti-veteran policy for all the veterans who entered Da Nang harbor.

The Court’s usual review is through a single judge decision. If the Court had just ruled on this case with a single judge then the decision would affect only Mr. Gray’s case. But this case was submitted to a panel. Therefore, this review will be precedential, meaning it will affect every other case where a veteran served on a ship that went into Da Nang Harbor. The February 25, 2015 oral argument before the Court can be heard here.

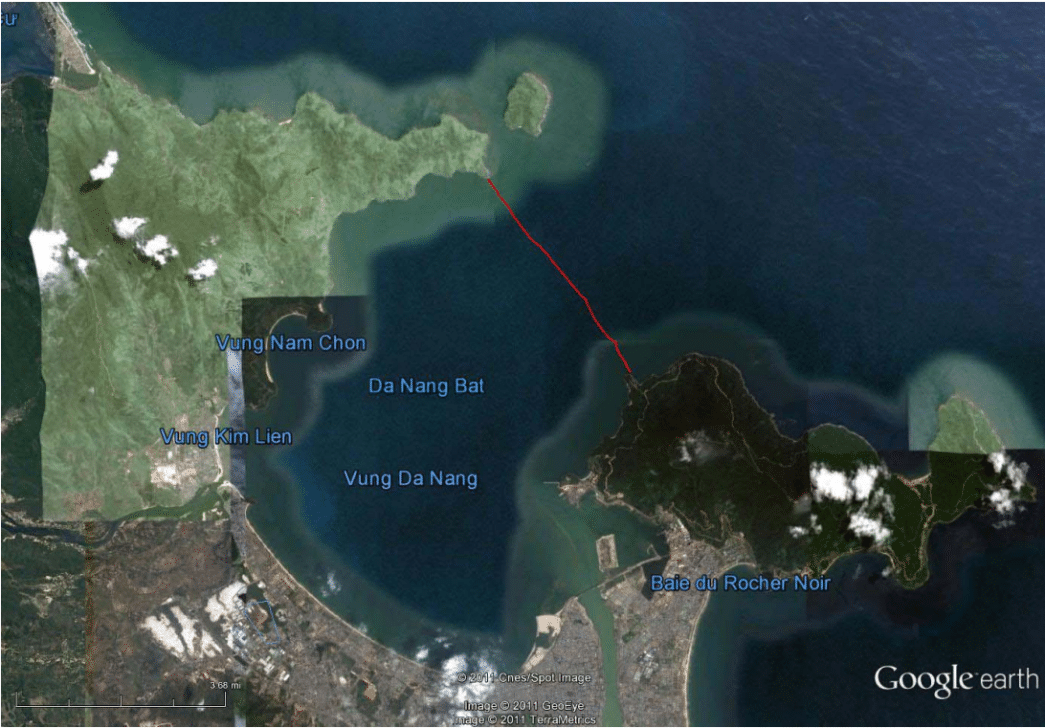

At the argument, we discussed various maps of rivers, deltas, bays and harbors in Vietnam. We believe that these maps make the VA’s policy of including some waterways as inland waterways and others as deep-water harbors plain as to its arbitrary nature. As we all learned in Haas case, which allowed VA to make a distinction between boots on the ground and blue water sailors for Agent Orange exposure cases, the Courts have to give deference to a policy where the VA has laid out its reasoning. But, we believe, that the VA failed to lay out any reasoning here.

Evidence That Could Help You

While developing Mr. Gray’s case we have collected evidence that could help any veteran entering a harbor in Vietnam, such as Da Nang, Vung Tau or Cam Ranh Bay. If you have a claim and you are in this same situation please download the attached evidence and get it in your C file.

- Obtain the deck logs of your ship if the VA has not done so already. You can start that process through the National Archives.

- This Supreme Court case, United States v. Louisiana, 394 U.S. 11 (1968)) defines what inland waterways are—including that a bay is an inland waterway.

- Download the maps of these bays and rivers, some of which VA deemed to be inland and others VA said were deep-water harbors. The importance of these maps is that you put all the waterways in front of the adjudicator and can argue that to say that there is no way to tell what method VA found some to be open water and others to be inland waterways.

- Get the Institute of Medicine’s report Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans and Agent Orange Exposure.

-

If you were in Da Nang harbor, then you need these affidavits:

10-6

10-7

10-13

These individuals can attest to the spraying of Agent Orange in and around the harbor and that the C-213 aircraft that was used to spray the Agent Orange across Vietnam were stationed at the Da Nang airport, which was under a mile from the harbor. - Also this document is an Amicus brief written by the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Association for the Gray case. Together with the Appellant’s Brief, it lays out the facts surrounding the use of Agent Orange in Da Nang. The Blue Water Navy website is filled with great information on this subject in general.

The VA’s reasoning for determining that Da Nang, Vung Tau and Cam Ranh Bays are not inland waterways is thin at best. VA points to its adjudication manual, the M21-1MR. The manual states that service aboard a ship anchored in an open deep-water harbor along the coast of Vietnam does not constitute an inland water way. The VA never defined what an open deep-water harbor is. As the pictures we used above show it is hard to tell why one bay an inland waterway and another is not.

Maps of Vietnamese Rivers and Bays

Background of the Da Nang Harbor Case

After decades of fighting veterans on the dangers of exposure to Agent Orange, Congress passed the Agent Orange Act of 1991 and forced the VA to admit that the chemical is not only harmful, but deadly, and that any soldiers on the landmass of Vietnam between 1962 and 1975 were exposed. But the VA draws a line in the sand, literally, when it comes to veterans who served offshore Vietnam in the Navy or Coast Guard. In fact, the VA has found that veterans who did not step onto land in Vietnam were not exposed to Agent Orange unless the veteran’s ship went into an “inland waterway.” In VA terms, this means that the ship went up a river, and the VA has explicitly taken a position that harbors are not inland waterways. This is a problem for Navy and Coast Guard veterans who served on ships that were anchored, and sometimes even docked, in Da Nang Harbor, a harbor in Vietnam that is surrounded by land on three sides.

Before we discuss the issues for veterans who were on ships in Da Nang Harbor during the Vietnam War, it is first important to understand how the VA treats Navy and Coast Guard veterans generally when it comes to Agent Orange claims. For Agent Orange claims in general, a veteran does not need to prove actual exposure to Agent Orange if he served in Vietnam during the period of January 9, 1962 to May 7, 1975 or along the Korean DMZ between April 1, 1968 and August 31, 1971. Under current VA policy, “service in Vietnam” means active military, naval, or air service which includes stepping foot on land or being on the inland waterways.

Things were different for naval veterans from November 1991 to February 2002, when the VA Manual M21-1 provided that unless there was evidence to the contrary, service in Vietnam would be conceded if the veteran’s service records show that he received the Vietnam Service Medal. This medal was often awarded to veterans who served on offshore waters, so proving receipt of the medal was a way for naval veterans to get the presumption of exposure and possibly get their claims awarded (if they suffered from a disease on the presumptive list). Even if a veteran was not awarded the medal, the manual required that the VA confirm that his ship was near Vietnam for a significant amount of time, not just passing through. Despite these guidelines, the VA was still not uniform in granting claims for so-called “Blue Water” veterans; some of these veterans were successful while others were not.

After years of inconsistency, the issue was finally addressed in 2006 in the case Haas v. Nicholson. In that case, CAVC sided with the Blue Water veterans and decided that they should receive the presumption of exposure to Agent Orange. Unsurprisingly, the VA appealed that decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. In a huge blow to Blue Water veterans, that court reversed the CAVC’s decision, and determined that the VA lawfully and reasonably changed the policy in 2002 to require service on land or on an inland waterway in Vietnam to be eligible for the presumption of exposure to Agent Orange (note that if a Blue Water veteran was awarded service connection between 1991 and 2002, the VA cannot apply the Haas decision retroactively and take service connection away from that veteran). As a result, if a Blue Water veteran wants to succeed with an Agent Orange claim, he must prove that he stepped foot on land in Vietnam or that the ship he served on went up a river. This can be shown through deck logs, personnel records, or even photographs.

So what does this mean for veterans who served on ships that were in Da Nang Harbor? According to the VA, these veterans are Blue Water veterans, and as a result must prove that they stepped foot on land or went up a river. But, there is a strong, reasonable argument to be made that the Da Nang Harbor is an inland waterway, and, therefore, those veterans are eligible for the presumption of exposure without proving they set foot on the landmass of Vietnam.

In fact, the Board of Veterans Affairs (BVA) reached that very conclusion in a decision from 2009. In that case, the BVA decided that “if the Veteran’s service had been limited to service on the U.S.S. Oklahoma City outside the territorial boundaries of the Republic of Vietnam, the presumptions … would be inapplicable to his case as he would not have met the criteria for service in the Republic of Vietnam. However … the Veteran’s service was conducted on a ship that frequently anchored in a harbor within the territorial borders of Vietnam. The evidence of record clearly shows that the Da Nang Harbor is well sheltered and surrounded on three sides by the shoreline of Vietnam. The harbor is nearly totally surrounded by land … As such, given the location of the harbor as being surrounded on land by three sides and the evidence that the harbor is within the territory of Vietnam, and resolving all doubt in the Veteran’s favor, the Board finds that Da Nang Harbor is an inland waterway for the purposes of the regulation.”

While this BVA decision should have been a huge win for Blue Water veterans, the VA has again been inconsistent in its treatment of naval veterans. Despite the fact that the BVA found in the above case that Da Nang Harbor is an inland waterway, in later cases it has found the opposite. Note that BVA decisions are not precedential, which means that the BVA is not required to follow their own decisions when it decides later cases. But, the BVA’s own rules do say that it strives for consistency in its decisions, and it is failing to provide consistency when it comes to veterans who served in Da Nang Harbor. It is difficult to see how Da Nang Harbor is an inland waterway for one veteran but not an inland waterway for another veteran. This raises substantial due process concerns, because the Constitution guarantees equal protection under the law, and two veterans who were both present in Da Nang Harbor should not be treated differently by the VA. This is not only unfair; it is completely arbitrary because the VA is not able to point to any authority other than its own internal policies as to why Da Nang Harbor is not an inland waterway.

In fact, in 1967, as part of the United Nations Law of the Sea Conventions, the boundary line of a nation’s inland water at the location of a harbor was defined as the line between the natural entry points to the harbor as long as the entry points are no more than 24 miles apart. The opening to the sea of Da Nang Harbor is only 4.24 miles wide, as illustrated below.

In addition, a Supreme Court case (United States v. Louisiana, 394 U.S. 11 (1968)) strengthens the argument that Da Nang Harbor is an inland waterway. In that case, the Court stated that “Whether particular waters are inland depended on historical as well as geographic factors. Certain shoreline configurations have been deemed to confine bodies of water, such as bays, which are necessarily inland.” Again, note that the VA is unwilling to provide any historical or legal authority to support its policy that Da Nang Harbor is not an inland waterway.

The BVA already made the correct decision one time, in the 2009 decision referenced above, and we hope that the VA will be forced to acknowledge that the Da Nang Harbor is an inland waterway so that veterans who served on ships docked there will be treated consistently and fairly. The arguments for Da Nang Harbor being an inland waterway greatly outweigh the VA’s internal policy that is nothing more than an arbitrary distinction.

The evidence above all comes together to demonstrate that the VA’s definition of inland waterway is arbitrary and capricious. There is no logic as to why one body of water is inland and other is not. The VA has the authority to interpret its own regulations but in doing so it has to offer both a legal and factual basis. It has not done so. This is the argument you should make in the VA with all the attached evidence.