Aside from making people sick, the COVID-19 pandemic has also had a massive impact on mental health for people across the globe. Feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression have become all too common. Upon surveying just over several hundred veterans and 500 or so civilians, our goal was to compare the state of their mental health during these trying times.

How did both groups fare before and during the pandemic? Are veterans taking advantage of state-sponsored services? How do the coping methods of veterans and civilians differ? These questions, and more, will help us identify key differences (or similarities) between them.

Then and Now

For starters, civilians and veterans were asked to rate the state of their mental health before the pandemic as well as during it. A small portion of both groups rated their mental health as poor before COVID-19 hit our borders, whereas most respondents felt that they were in a good state of mind.

Since the pandemic started, though, veteran responses were fairly similar whereas civilians have been feeling slightly more impacted – there was a 5.9% uptick in them categorizing their mental health as poor. Although wartime experience can have troubling effects on veterans, it may also make them more resilient when dealing with stressful situations. Their ability to cope with adversity can be a valuable asset at a time like this to remain calm and positive. Interestingly, before the pandemic, civilians were more likely to have attended some degree of mental health therapy than veterans.

The Impact of Isolation

Among the many challenges that we’ve had to face in the wake of COVID-19, loneliness has had the biggest negative effect on both civilians and veterans’ mental health. A survey completed by 10,000 adult workers in early 2020 showed that more than 3 out of 5 Americans felt lonely, which equated to nearly a 13% rise from 2018 when the same study was conducted for the first time.

Looking specifically at veterans, only 24.3% said they socialized with other veterans through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) prior to the pandemic. Veteran Allen Murphy has had a tough time without his usual social gathering at the VA – he says he feels lonely and depressed due to the pandemic, Allen is only able to go participate in his favorite VA-organized activities once every two weeks. Even though many veterans said they haven’t engaged with the VA’s social offerings, the pandemic has been especially hard for people like Allen who find their programs essential for many aspects of their well-being.

Generally, most veterans didn’t see the value in socializing with over veterans – 33.1% of them believed it was not important at all, and 26.2% thought it was slightly important. The remaining 31.7% either felt it was somewhat (17.7%), moderately (14.1%), or extremely important (8.9%).

On Trauma

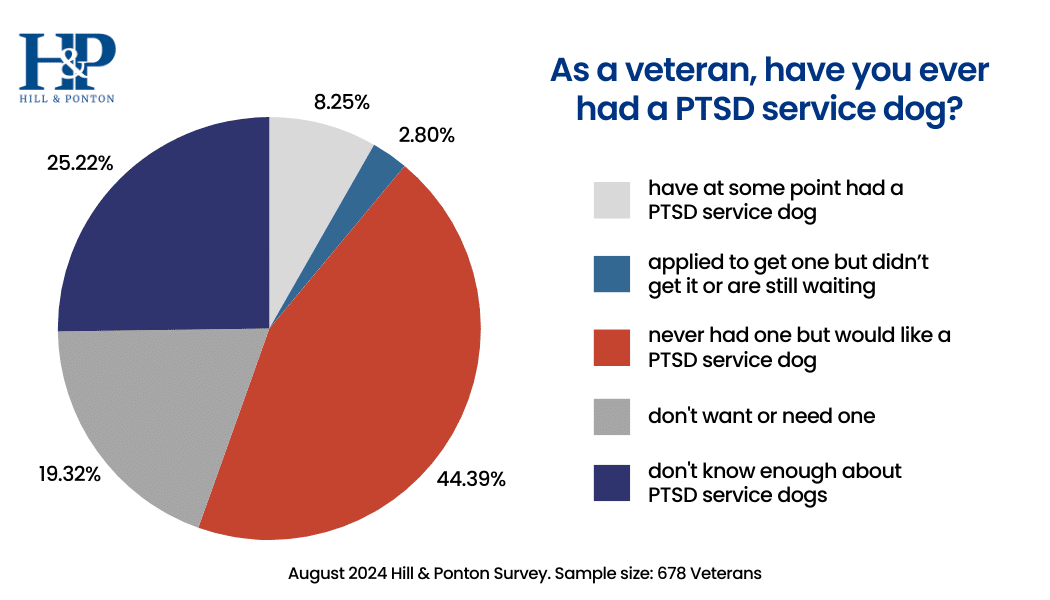

Regarding PTSD, 42.3% of veteran respondents said they had suffered from some form of it in relation to their time in active duty. The pandemic increased the frequency of PTSD episodes among veterans who suffer from it, as 60.6% of them had experienced an incident due to COVID-19.

The pandemic can specifically trigger PTSD in veterans for a few reasons. People generally feel more unsafe, and these concerns can be more intense for them than others. Their trauma can be triggered as well – for example, the narrative of fighting the pandemic as if it is a war may bring up many uncomfortable feelings and memories from someone’s time on duty. Generally, the pandemic can increase people’s negative thoughts – this might manifest into the feeling of being out of control and lacking trust in others, which could be very disorienting and triggering for veterans.

Getting Through It

To cope with the pandemic, both veterans and civilians used TV and movie watching as an outlet the most. Veterans, however, were more likely than civilians to play video games as a coping method (30.5% compared to 24.1%). According to Dr. Melanie Mousseau, vice president of programs and operations for a charity/veterans service organization called Wounded Warrior Project, there has been an uptick in veterans playing video games to keep their mind off of stressful thoughts and as an effective outlet to release anger.

Veterans were also more likely to productively spend their time by being outdoors/in nature, staying in touch with friends, reading, and limiting intake of the news, which rarely has positive updates these days.

Final Thoughts

Overall, there are some key differences between veterans and civilians on the topic of mental health. For example, once the pandemic started, civilian mental health became noticeably poorer, whereas veterans seemed to remain more stable. One similarity, though, is that the same number of civilians and veterans scored their top coping strategy as watching TV and movies and ranked the others fairly alike.

Veterans, in particular, have had an interesting response to the pandemic. Due to the sensitivity and strain of the situation, those with PTSD could struggle with increased symptoms and episodes. On the other hand, their wartime experience could also help them remain calm due to the courage and resilience to adversity they’ve developed. At a time like this, the most courageous thing someone could do is seek the help they need. The folks over at Hill & Ponton fight for veterans every day – let them fight for you. To learn more about their mission, head over to their website now to get the care and justice you deserve.

Methodology

We surveyed 305 U.S. military veterans and 511 civilians about the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on their mental health. Veteran respondents were 75.4% men and 23.3% women. Three respondents were nonbinary, and one chose not to disclose their gender. The average age of veteran respondents was 42.1 with a standard deviation of 14 years.

Civilian respondents were 48% men and 51.3% women. Three respondents were nonbinary, and one did not disclose their gender. The average age of civilians surveyed was 38.6 with a standard deviation of 11.9 years.

Only veteran respondents who reported ever experiencing PTSD were asked specifically about PTSD episodes since the beginning of the pandemic.

Questions about coping mechanisms used during the pandemic were formatted as check-all-that-apply questions. Therefore, percentages won’t add to 100.

Limitations

The data we are presenting rely on self-report. There are many issues with self-reported data. These issues include, but are not limited to, the following: selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and exaggeration.

Fair Use Statement

The pandemic has been rough on the mental health of everyone, but the nature of military service can add an additional factor to mental health management. If someone you know would benefit from the information in this project, you may share it for any noncommercial reuse. We ask that you link back here so the entire project and its methodology can be viewed. This also gives credit to the contributors who make this work possible.